Hey there!

I’m Suzie, one of the BizLab fellows that worked this summer to find additional sources of revenue for WBUR, with the goal of identifying new opportunities for public radio funding.

Merchandise has been a strategy for arts and nonprofit organizations for years. It gives companies with intangible products and services a way to become tangible and to broadcast their branding via clothing and household items. Organizations like EveryTown for Gun Safety broadcast their message through their advocacy T-shirts and New York City’s High Line sells tea towels with the route etched down the center.

Public radio organizations provide many more examples of how to incorporate retail merchandise into the listener experience. NPR’s Planet Money made an entire segment about the journey of a shirt from creation, to purchase, to disposal, which you can access here. Moreover, NPR itself has a full-time merchandise website, alongside This American Life, and Minnesota Public Media. Other public radio stations have adopted the “Pop-Up Shop” model, including Chicago’s NPR station, WBEZ. Here at WBUR, there has been talk of one for years, with ideas and designs floating around different departments without an outlet other than pledge drives to put them out to the public.

That’s where BizLab comes in! Joan DiMicco, our director and fearless leader, wanted to see if a merchandise store could be an alternate channel for profit for WBUR. She then needed someone to take the idea and turn it into a physical experiment. WBUR was also interested to see if this could be a job handled by one staff member dedicated to the store. This is where I come in!

In the public radio industry, the exchange of goods occurs usually during pledge drives and live events. Items are either given away as swag for promotional or relationship building purposes or given as a gift (a “premium”) in return for a donation that is larger than the market value price of the item. A merchandise store challenges that model by changing the exchange from a two-way gift to a transaction. This both reduces the barriers to entry for ownership of WBUR branded items and increases them. No longer will people be paying $120 a year to get a T-shirt, but in the same vein, no longer will people be able to walk up to a table and take a shirt home for free. In this venture, people will enter a virtual marketplace and buy items for an average retail price.

We began the summer with a few core questions:

- Is there a market for non-pledge related merchandise?

- Are people interested in JUST WBUR branded merchandise (i.e. no catchy public radio slogans)? Which items do people like?

- Who will be the most engaged audience for the Pop-Up Shop? (age, gender, geo, and donor status)

- Is a merchandise website a profitable venture for WBUR?

In order to conduct this experiment and answer these questions, we went from concept to a fully functional e-commerce business in less than 12 weeks. Our strategy had 5 steps:

In this blog post, I will talk about the first 3 steps: Ideation, Partners, and Implementation.

Step 1: Ideation

During my first week at WBUR, we were present for an event for the WBUR “Sounding Board”, which is a group of young people who listen to WBUR who come to offer feedback on programs put on by the station. We learned first-hand why people donate and, more importantly, why they don’t. Later in the week, we met with a consultant named Sarah Bloomer to kick off some brainstorming for each of our experiments. Here, we determined that the way to visualize our own store would to be by a) differentiating, b) mimicking, and c) understanding consumer demand.

In terms of differentiation, we wanted to make sure that people understood that this was not affiliated with a pledge drive, and thus not entirely related to membership. We wanted to avoid this because of the existence of premiums. If we did not explain that this was a for-profit venture within the business laboratory of a non-profit, it could be possible that current members would feel cheated out of merchandise that they paid larger amounts of money for. Through this realization, we decided to avoid using any inventory we already had, and design brand new pieces. Continually, a lot of the WBUR merchandise itself is tied to a pledge drive, be it a marathon shirt with the date on the back or a dated slogan from a past fundraiser. This gave us the opportunity to test whether there was a market for solely WBUR branded items.

While we were looking to set ourselves apart from pledge drives and other public media outlets, we also needed to learn what was working for them. We researched various websites that sold merchandise to see which items were the top sellers, the price points, and the amount of inventory for each. WBUR has done a few fundraisers that have a similar model to a purchased based campaign, so we consulted with the membership department on their tactics for success.

As more and more people caught wind of our venture, the suggestions for items began pouring in. We quickly realized that there was also an opportunity to test which items would work best for WBUR’s audience. But that also begs the question, which audience? At WBUR, if you donate to the station you are considered a member. The membership of WBUR is split about 60/40 women and men, and the average listener of the station is in their 50s. Could a merchandise store be an opportunity to get non-members to support the station by eliminating the high premiums, or would it attract mostly people who already support?

Before we even began conducting our experiment, we found the need for another experiment.

Thus, the WBUR Summer Pop-Up Pre-Order was born! This took the shape of a Google Form, placed as an ad in our daily/weekly e-mails to subscribers and sent out as a Facebook ad to different selections of WBUR supporters. Inside the form, I placed 12 designs for various items from notebooks to T-shirts to water bottles, and even a WBUR (pronounced wubber) ducky. Some of the designs I came up with myself, while others were previously mocked up by a woman named Lillian in membership (who is on maternity leave, thank you Lillian!) just in case an experiment like this was ever to happen.

The Pre-order form was live for about 10 days and offered a 10% discount to anyone who entered their e-mail. We had 63 people fill out the form, and they ordered a total of 111 items. Of the 12 items, there were 6 that were clearly the best sellers, comprising 77% of all orders.

We were surprised to see that they were mostly T-shirts! Around the office, everyone said they wanted anything BUT a WBUR T-Shirt, but once the results came in we could not argue with the market. Marketing testing FTW! Going with our gut would have resulted in a store of dog bowls and rubber duckies.

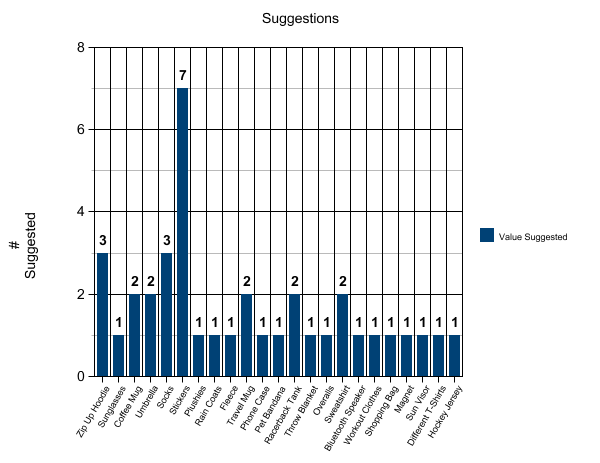

We added a suggestions box at the end of the form for people to tell us what they wanted to see, and these are a few of the results.

Because we already gave away stickers for free in our office, we decided to avoid selling them (differentiation!) for this iteration of the project. The final 6 items selected from the pre-order form went on to become the 6 items we offered “in store”.

Step 2: Partners

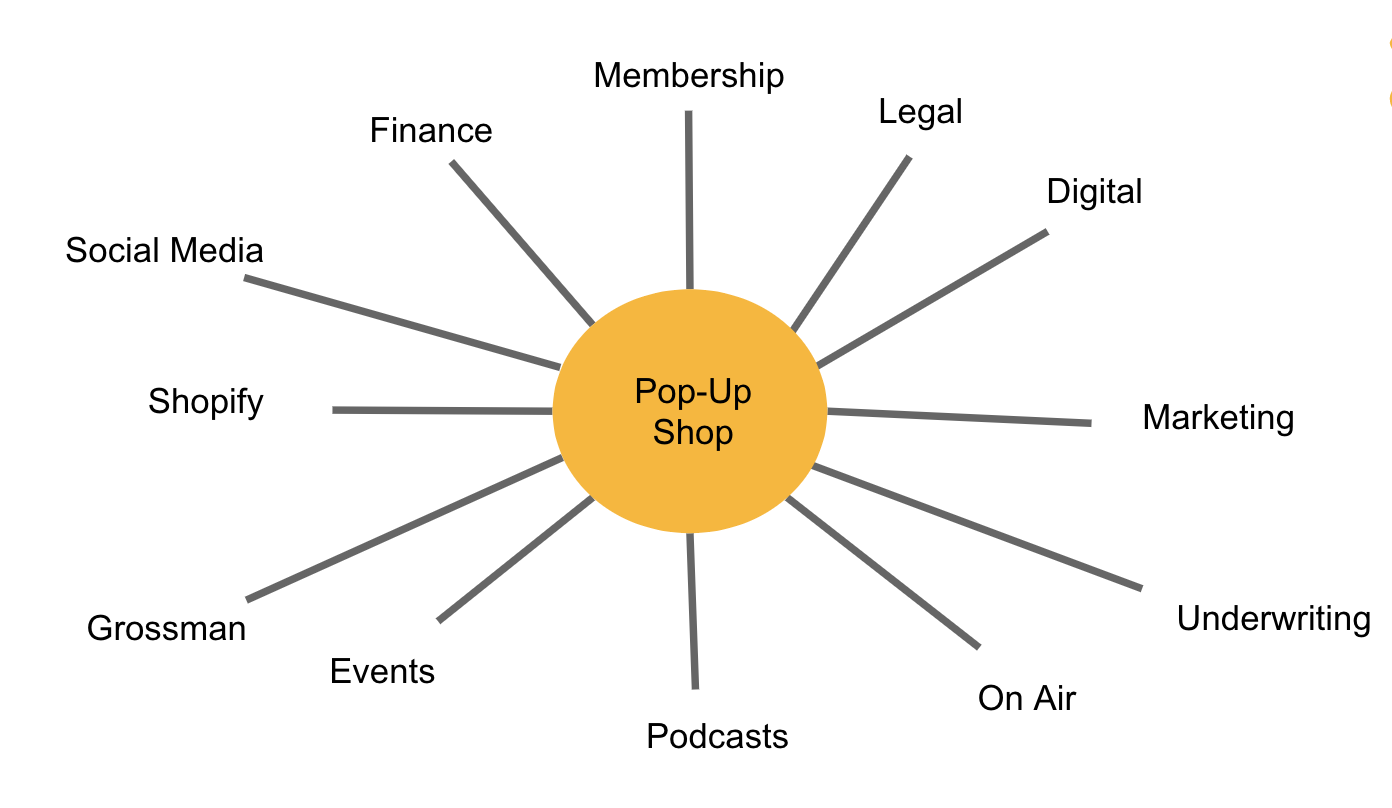

Here is a diagram of all the different departments/companies we worked with to complete this experiment.

In order to create a functioning e-commerce business, we needed to have a) things to sell and b) a place to sell them. The designs I put on the pre-order form were just proofs mocked up in our own office, so we needed to find someone to turn them into tangible goods. At the beginning of the summer, the membership department had asked us about our plan for fulfillment, because during pledge drives they usually ship everything out themselves. Joan and I agreed that we would rather have a shipping and fulfillment service outside of the creepy basement, so we contacted Grossman Marketing, a well-known marketing firm in Somerville that has historically supplied goods for our pledge drives. They were able to design, procure and fulfill our orders in a sustainable, local manner.

The next step was to find a host for our site. We contacted different e-commerce platforms and eventually settled on Shopify based on the cost and the UX of their design tools. We selected the basic plan ($29.99/month with percentage fees of purchase) and were able to begin designing immediately.

Once the external partners were settled, we looked inward to get the funds and allowances to continue. Because WBUR is an affiliate of Boston University, any contracts we signed or terms and conditions we clicked were a liability to the school. We thus worked closely with BU’s legal department to verify Shopify’s terms of service, make sure Grossman was on the list of approved vendors, and to create our own terms of service for the site. We also worked with WBUR’s financial department to set up a payment gateway between Shopify, BU, and WBUR that would place the money in the appropriate accounts. The digital team got us the domain name for our site, and the membership team gave us parameters for customer acquisition and analysis. Our other partners helped mostly with promotion, which I will explain further in my next post.

With all the necessary approvals in place, it was time to design.

Step 3: Implementation

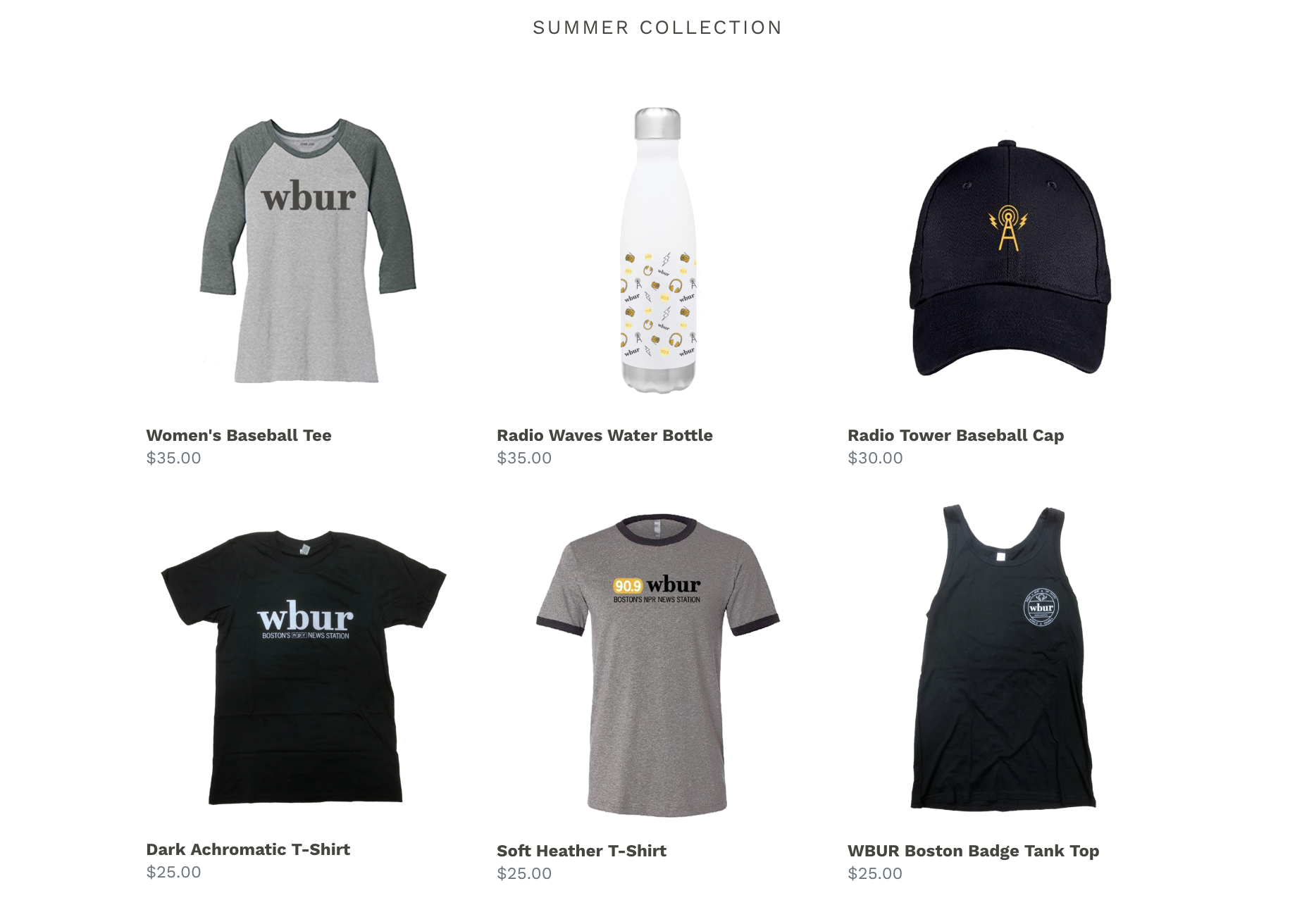

Shopify makes designing an e-commerce website incredibly easy. They have really done their homework in terms of all the pieces necessary for a customer to have a fulfilling experience on a site. It basically creates a generic template for you, complete with contact pages, E-mail confirmation, inventory records, and animations. All you have to do is customize it to your brand. My main job while designing was creating an overall aesthetic of the shop, writing copy for the items and figuring out a way to display the products while not actually having any physical products yet. If you are reading this post any time after August 24th the shop will already be closed, so here are some screenshots of what it looked like.

I worked with Grossman on ordering the items while I was designing the site. Joan and I came up with some revenue projections based on hypothetical profit margins as well as projected demand, based on the pre-order form. We projected that if we sold ~90% of our inventory, we would make about $6,000.00 in profit. Between the 6 pieces we designed, we stocked the store with 900 items.

The store was fully functional and ready to launch by July 19th, but a few items were on back order, and the legal department at BU was concerned about a few pieces of Shopify’s terms of service. This stalled our launch until the following week, but because we had scheduled the marketing to go live on the launch date, we were able to overcome the blockades.

The store itself launched on July 24th, 7 weeks and 1 day after planning began.

Check back into my next two blogs to learn about the promotions and analysis of the project!